Over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives are important financial transactions that allow hedging of interest rate, foreign-exchange and other risks. However, they can be quite complex and the embedded counterparty risks must be understood and managed carefully. This, in turn, requires a careful understanding of all of the contractual terms to the OTC derivative contracts.

In this blog post, we’ll cover important contractual terms that are typically applied to OTC derivatives transactions, including:

- The ISDA Master agreement

- Close-out amount

- Netting

- Termination features and resets

- Central counterparties & bilateral rules

The ISDA Master Agreement

The market standard for OTC derivative documentation is the ISDA Master Agreement. The master contract is made up of a common core section and schedules containing adjustable terms that can be agreed upon by both parties. The terms specify contractual obligations such as netting, collateral, termination events, the definition of default and the close-out process.

The commercial terms of individual transactions are documented in a trade confirmation, which references the Master Agreement for the more general terms.

From a counterparty risk perspective, the ISDA Master Agreement has the following key features:

- events of default and the mechanics of the resulting close-out process;

- the application of netting with respect to different transactions in the event of default; and

- the contractual terms regarding the posting of collateral.

Close-out Amount

The close-out amount represents the quantity that is owed by one party to another in a default scenario. If this amount is positive from the surviving party’s point of view, they will have a claim on the estate of the defaulting party. If it is negative, then they will be obliged to pay this amount to the defaulting party.

Establishing the size and nature of a claim is crucial – although the defaulting party will be unable to pay it in full. The surviving party will likely consider the cost of replacing transactions. The defaulting party may naturally disagree with this assessment since it will reflect charges such as bid-offer costs.

The concept of replacement cost led to the development of "Market Quotation" as a means to define the close-out amount in the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement, and an alternative called the “Loss Method”.

These can be defined as follows:

- Market Quotation. The determining (surviving) party obtains a minimum of three quotes from market-makers and uses the average of these quotations to determine the close-out amount.

- Loss Method. This is the fallback mechanism in the event that it is difficult for the determining party to use Market Quotation. The determining party is required to calculate its loss in good faith using reasonable assumptions.

Market Quotation has been a great success for simple transactions in relatively stable market conditions, but it's drawbacks became apparent in more complex transactions. Since 1992 the numbers of complex and structured OTC derivative transactions have increased. This led to a number of significant disputes and the Loss Method was viewed as too subjective and as giving too much discretion to the determining party. Contradictory decisions made by the English and US courts further complicated the matter.

The 2002 ISDA master agreement replaced the concepts of market quotation and loss method with a single definition called "close-out amount." Close-out amounts are essentially diluted forms of actual tradable quotes because they do not require any tradable quotes, but can use indicative quotations, public sources of prices and market data, and internal models to arrive at a commercially reasonable price.

The close-out defines the economics of counterparty default and is thus a crucial element in defining credit exposure. For example, under ISDA 2002's definition, the determining party’s own credit worthiness and costs of funding and hedging may be included.

Netting

OTC derivatives markets have historically developed netting methods to facilitate the offsetting of what one party owes another. The following two mechanisms, which apply in both bilateral and centrally cleared markets, facilitate this:

- Payment netting. This gives a party the ability to net cash flows occurring on the same day sometimes even if they are in different currencies. This typically relates to settlement risk since it mitigates intraday risk.

- Close-out netting. This allows the offsetting of all transaction values (both in a party’s favour and against it) in a default scenario. This typically relates to counterparty risk.

A close-out netting gives a surviving party the right to offset all transactions and determine how much they are owed. This is done by adding up positive and negative values to determine the net balance for the final close-out amount.

In essence, all covered transactions (of any maturity whether in- or out-of-the-money) collapse to a single net value. If the surviving party owes money, then it makes this payment or if it is owed money then it makes a claim for that amount.

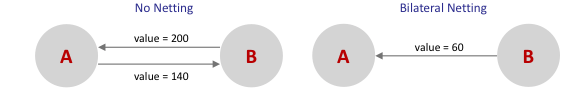

The advantage of close-out netting is that it allows the surviving party to immediately realise gains on transactions against losses. This means they can effectively jump the bankruptcy queue for all but its net exposure, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Illustration of the impact of close-out netting. In the event of default of party A, without netting, party B would need to pay 200 to party A and would not receive the full amount of 140 owed. With netting, party B would simply pay 60 to party A and suffer no loss.

In the event that a defaulted transaction occurs in OTC markets, survivors will usually attempt to replace it with another agreement. Without netting the total number of transactions and their notional value that surviving parties would attempt to replace may be larger and thus more likely to cause market disturbances.

In centrally cleared markets, netting is potentially more efficient by being multilateral, rather than bilateral. However, bilateral markets do achieve multilateral netting via “portfolio compression”. Initiatives such as TriOptima’s TriReduce service[2] provide compression services covering major OTC derivatives products.

This is done by coordinating a reduction in transactions between major market participants but without materially changing their net market positions. Since compression services reduce the number and gross notional of financial derivatives, they are also complementary to central clearing environments.

Termination Features and Resets

In addition to netting, some other features that are applied at the transaction level and help mitigate risk include:

Termination Events: an Additional Termination Event (ATE) is an additional term that allows a party to terminate the OTC derivative transaction in certain situations. For example, if their rating has been downgraded below investment grade levels. A termination event can be mandatory or optional.

ATEs are designed to reduce counterparty risk by allowing a party to terminate transactions or apply other risk-reducing actions (for example, receiving collateral) when their counterparties credit quality is deteriorating. Variants include “break clauses” and "mutual puts".

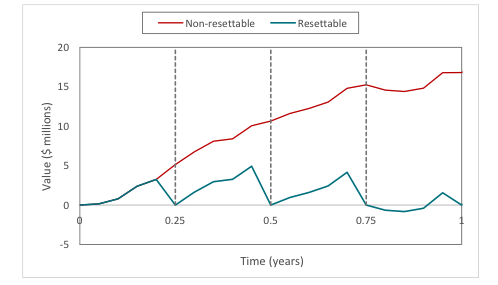

Resets: a reset agreement is a clause which avoids a transaction becoming strongly in-the-money (to either party) by means of adjusting product-specific parameters that reset the transaction to be at-the-money. Reset dates may coincide with payment dates or be triggered by the breach of some market value. For example, a resettable cross-currency swap is a financial product where the current value (mostly driven by FX movements) can be cash settled at each reset time and the FX rate is reset (by adjusting the notional of one leg) to (typically) the prevailing spot rate.

A reset is similar to the impact of terminating a transaction and then executing a replacement transaction at market rates, so it reduces exposure. An example can be seen in Figure 2 - It can also be seen as a first step towards collateralisation.

Figure 2. Illustration of the impact of reset features on the exposure of a long-dated cross-currency swap. Resets are assumed to occur quarterly.

Collateral

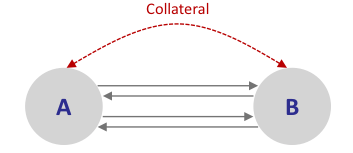

Collateral is an asset supporting risk in a legally enforceable way. The fundamental idea of collateralisation (Figure 3) means passing cash or securities from one party to another with the goal of reducing counterparty risks. Whilst break clauses and resets can provide some risk-mitigating benefit in these situations, collateral is a more dynamic and generic concept.

Figure 3. Illustration of the basic role of collateral in OTC derivatives.

Collateral agreements reduce risk by providing collateral to support an exposure. In the event of default, the surviving party can use the collateral to offset any losses. Note that collateral agreements are often bilateral, so you'll need a counterpart who is willing and able to post their own in case there's negative exposure. So in the case of a positive value, a party will call for collateral and in the case of a negative value, they will be required to post collateral themselves.

Some important terms in collateral agreements are:

- Threshold. The threshold is an amount below which collateral is not required, leading to undercollateralisation. Above the threshold, only the incremental amount of collateral can be called for (for example, a threshold of 5 and value of 8 would lead to collateral of 3 being required). Thresholds limit the risk reduction benefit of collateral but reduce the operational burden and liquidity costs. Zero thresholds are increasingly common.

- Minimum transfer amount (and rounding). A minimum transfer amount is the smallest amount of collateral that needs to be transferred. It is used to avoid the workload associated with a frequent transfer of relatively insignificant amounts of collateral.

- Haircuts. A haircut is a reduction in the value of an asset to account for the fact that its value may fall when it is liquidated. As such the haircut is theoretically driven by the volatility of the asset, and its liquidity. Haircuts are primarily used to account for market risk stemming from the price volatility of the type of collateral posted although collateral with significant credit or liquid risk is generally avoided.

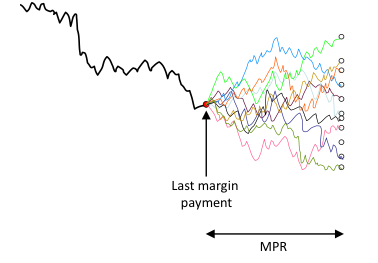

The margin period of risk (MPR) is the time between when a counterparty ceases to post collateral and when all the underlying transactions have been successfully closed-out and replaced (or otherwise hedged), as illustrated in Figure 4.

Such a period is crucial since it defines the effective length of time without receiving collateral where any increase in exposure (including close-out costs) will remain uncollateralised. It is often used when modelling the effects of collateral.

Figure 4. Illustration of the role of the margin period of risk (MPR).

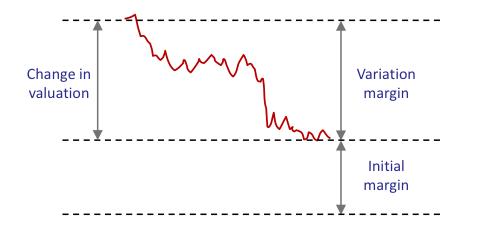

There are two different types of collateral. In derivatives, collateral would most obviously reflect the value of the underlying transactions, which can generally be positive or negative from each party’s point of view. This idea forms the basis of variation margin.

In a default scenario, the variation margin may not be enough due to delays in receiving collateral and close-out costs, e.g. bid-offer. For these and other reasons, initial margin is sometimes used as additional collateral. Figure 5 shows conceptually the roles of variation and initial margins. Clearly, the MPR concept is related to the initial margin amount.

Figure 5. Illustration of the difference between variation and initial margins. Variation margin aims to track the value of the relevant portfolio through time whilst initial margin represents a buffer that may be needed due to delays and close-out costs.

Initial margin (or independent amount) is the amount of extra collateral that must be posted regardless of what happens with the value of the underlying portfolio. The general aim behind it is to give you added safety, in case there are any risks like delays receiving collateral and costs in the close-out process.

Initial margin has been fairly uncommon in bilateral markets although future regulatory rules will change this.

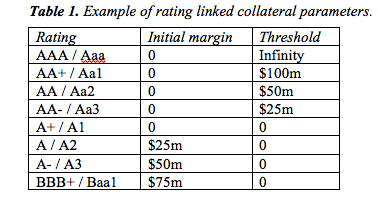

Note that thresholds and initial margins work opposite to one another: an initial margin can be thought of as a negative threshold, (intuitively and mathematically). Historically, OTC derivatives markets have sometimes also linked collateral requirements to credit quality – most commonly credit ratings. An example of this is shown in Table 1.

Two other important concepts in collateral management are:

- 1. Rehypothecation. For funding reasons, it is useful to re-use collateral although this tends to create counterparty risk. The right of rehypothecation means that the collateral receiver can use the collateral, for example, in another collateral agreement or a repo transaction. In some situations, such as posting cash variation margin, rehypothecation rights are not required since the collateral is intrinsically reusable.

- 2. Segregation. Segregation of collateral is another way to reduce your counterparty risk and may be achieved through legal terms or alternatively with the help of third party custodians holding the initial margin. It involves collateral posted being legally protected should the receiving counterparty become insolvent. Segregation is contrary and incompatible with the practice of rehypothecation.

- In general, variation margin (since it is an amount owed) is not segregated and can be rehypothecated. Initial margin (since it is an additional amount) is usually segregated and cannot therefore be rehypothecated.

Central Counterparties and Bilateral Margin Rules

The global financial crisis from 2007 onwards triggered grave counterparty risk concerns. It was catalysed by events like the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, failure of monoline insurers and default in Icelandic banks to provide loans that were needed for businesses around Europe.

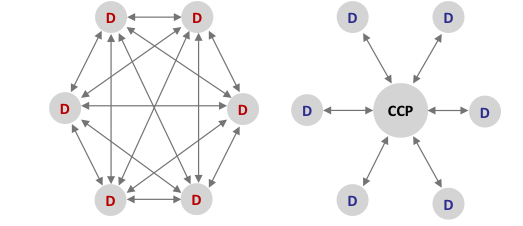

Counterparty risk in OTC derivatives, especially credit derivatives, was identified as a serious risk to the financial system. This led to regulation demanding that all standardised OTC derivatives be cleared via central counterparties (CCPs).

The main function of an OTC CCP is to act as the middleman between counterparties. By acting on both buyer and seller sides, they can assume each party’s rights or obligations. (Figure 6).

This means that the original counterparty to a trade no longer represents a direct risk. The CCP becomes the new counterparty to a trade, and they reallocate default losses via a variety of methods including netting, collateralization and loss mutualisation. Obviously, this process aims to reduce counterparty and systemic risks.

Figure 6. Illustration of bilateral markets (left) compared to centrally cleared markets (right).

Some banks and many end-users of OTC derivatives (e.g., pension funds) access CCPs through a clearing member instead of becoming full members themselves. This is due to the membership, operational and liquidity requirements related to being a clearing member. In particular, participating in regular “fire drills” and bidding in a CCP auction are the main reasons why a party decides against being a clearing member at a given CCP. Acting as a clearing member for a client creates a potential exposure in the event the client defaults.

Financial regulators now require that major OTC derivative users are subject to a system of bilateral margin rules governing how they post collateral. From September 2016 these rules were phased in, and require financial counterparties to post variation margin (with zero thresholds) or initial margin to each other.

The intention seems to be to make the bilateral collateral rules quite close to those required by CCPs. The initial margin required by the bilateral margin rules is generally required to cover potential losses to a confidence level of 99% over a time horizon of 10-days.

Such initial margins are typically based on quantitative models calculating this requirement as a statistical quantity. The results of initial margin amounts can then vary quite substantially with market conditions.

For those interested in gaining a more in-depth understanding of OTC derivatives contracts, please contact us. Jon Gregory’s course Bilateral Margining and Central Clearing provides an expert overview with everything you need to know on the topic.

Our team is committed to providing specialised teaching and resources on derivatives so that our customers can stay ahead of the curve with their investments or work-related projects. Whether your interest lies in trading stocks or drawing up sophisticated financial contracts, you will find what you need among our course offerings.

Related Courses

Bilateral Margining and Central ClearingValuation Adjustments: The XVA Challenge

[1] The calculations made by the surviving party may be later disputed via litigation. However, the prospect of a valuation dispute and an uncertain recovery value does not affect the ability of the surviving party to immediately terminate and replace